Major disasters such as those caused by earthquakes, typhoons, floods, fires, volcanic eruptions or tidal waves (tsunami) are a preoccupation throughout Japanese history. They have left the Japanese with a profound sense that impermanence is the only permanent feature of life.

The list of disasters which has struck Japan is longer than need be related. Even in the 20th century, natural disasters like the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake which killed more than 100,000 people have reinforced the sense of impending catastrophe. When a volcano kills people, as did Mt. Unzen at the start of the 1990s, many a head nods in agreement that Japan is typified by instability, not only in respect of the physical environment, but all aspects of existence.

Man-made disasters contribute to the sense of foreboding. The many successes of the late 19th and early 20th centuries were virtually erased by the damages of World War II. Even well into the “economic miracle” of the post-war period, the oil boycott of the Arab states in 1973 which resulted in high inflation and economic restructuring reinforced many in the opinion that Japan was fragile, subject to sudden wrenches and sickening downturns. Only in the 1980s and early 1990s was this feeling apparently sloughed off, but the recession of 1992-93 caused a return to a gloomy aspect.

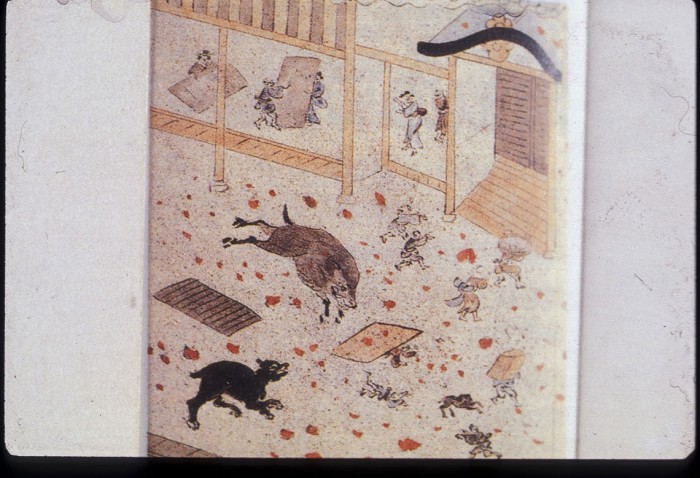

While disasters give rise to a degree of pessimism, especially well expressed in literature and poetry, the effect should not be over-estimated. Disastrous fires led city dwellers in Edo, for example, to maintain large stocks of lumber in safe areas close to the city center so that entire districts could be rebuilt within weeks. Even after the 1923 earthquake in the Kanto area, rebuilding was quick because of this tradition. It was said that a business which could not be reopened within three days of a fire was a poorly managed one that was destined to fail anyway.

The tradition of disasters has created a speculative vigor which revels in the anticipation and fact of disaster just as much as it feeds an instability and pessimism.

A related article concerning the sense of being the “victims of disasters” among some Japanese is available at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.The article summarizes a presentation by Michael Schaller and discussion by Ian Buruma about the cultural impact of the series of Godzilla movies.