The traditional meal centers on rice to such an extent that the word gohan means both rice and a meal. Rice was the main dish and was eaten in great quantities with side dishes of vegetables, meats, and soy bean-products supplementing the main course. In modern times, however, rice has declined in importance as prosperity brought to the table more and more side dishes. Today, the side dishes are really the main dishes and rice is eaten in small quantities.

Traditional foods are often presented in a manner calculated to please the eye as well as the stomach. Ways to cut food attractively and careful preservation of the original flavor of food has brought to Japanese cuisine a high reputation for aesthetic beauty. This influence can be traced back to the Imperial court where the refined presentation of food was as important as the taste.

Vegetarian influences are also very strong in Japanese food. The large number of delicious vegetable dishes reflect the wide variety of vegetables grown, some of them imported from the Asian mainland or the West. Bean curd, presented in a bewildering array of guises, was brought to Japan by Zen Buddhism. Little oil, and only vegetable oil at that, is used in traditional cooking, another factor which gives Japanese food a reputation for being healthy.

Family-style cooking, however, is considerably different from the high culture of the Imperial court and the austerity of the Zen monks. A banquet might have rice and a dozen or more small side dishes for each guest, but an ordinary family would have far simpler food in both presentation and number of dishes. In the Edo period, this simplicity plus poverty saw many farmers eating rice (if they were fortunate, barley or barley mixed with rice if times were hard), a few pickles, and some vegetables.

Meat was seldom eaten until the middle of the 19th century. Buddhism discouraged eating meat from 4-legged animals, so fish is the primary meat in traditional cooking. Thus, for both Japanese and foreigners, sushi and sashimi are often considered the best in Japanese cuisine. With all the other cultural influences from the West, however, came Western food and cooking. Meat has now become such an important part of the menu that tonkatsu (pork cutlets) is firmly established as a “Japanese” food while steak, fried chicken, and hamburgers are common. With the introduction of Western food came cooking styles that required more oil and fat. One result has been to change vastly the content of Japanese meals, but another is to bring to Japan the health hazards of the Western diet: high cholesterol and obesity, in particular.

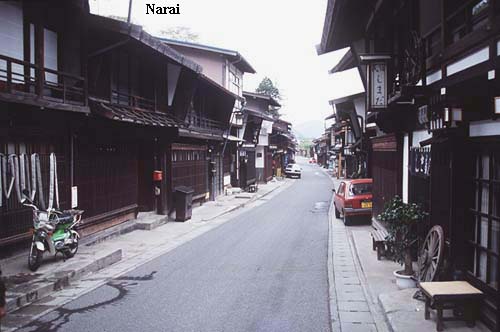

Food is of such immense concern that many travel guidebooks are entitled “. . . tabearuki” or ‘Eating and walking around . . . .’ Each locale takes pride in some local delicacy prepared in a particular manner. In Narai for example, special cakes made of glutinous rice and flavored with herbs are the local delicacy. Even in the late 19th century, in Hosokute, according to Ernest Mason Satow’s A Handbook for travellers in Central and Northern Japan:

‘the traveller should be careful to ask for a tsugumi (a sort of thrush) preserved in yeast (kojidzuke), which when slightly roasted is delicious and forms a welcome addition to the ordinary fare in a region where fresh fish is scarce.’